I delivered Passion Plays as Monki Gras 2025, an unique and intimate conference on software, craft, and tech culture. This year’s theme was “Sustaining Software Development Craft”.

You can find the slides here. Below is the original script.

Introduction

I am currently based in Spain - been there for going on four years, after spending over a decade between Bucharest and Berlin.

Being in Madrid I’ve taken advantage of the fact that, since there is quite a bit of production around the community of Madrid, you can more easily have access - or at least a connection - with the people who make the things that you consume on a regular basis, which is something I hadn’t even realized I hadn’t had for a good twenty years.

Since I’m something of a wine guy, I take every chance I get to meet the wine makers who make the stuff that I end up drinking, and talk to them about their process, their choices, the tradeoffs that they have to make, the risks they take.

Let me tell you - if there’s a job that involves passion, it is wine making.

Now, I don’t mean passion in the sense of “feeling this all-compassing, fiery love for what you do”, which gets talked up enough in general media.

It does require love and dedication, though, because I mean it in the original Latin sense, of passio, meaning suffering.

And talking to these people has made me realize that… damn, when it comes to project sustainability, we have it easy in the software industry.

Disclaimer

You do you

Before we get going, though, I want to say: none of this is prescriptive. I know that when I start going on I can come off as preachy or soapbox-y. That’s just me being me.

You do you. Alright?

Nature interferes

Suppose you want to start a wine project.

So you go out, you buy land with some old vines (which are rare, but I won’t get into why now, because that’s an entire rabbit hole), and you set to work.

While from the outside it seems like a steady, season-driven business, you are subject to all sorts of issues outside your control.

The Plagues of Iberia

Mildew can rot your plants, frost can kill your grapes. Too much sun? Dead. Too much water? Probably dead. (Or at the very least the quality of your grapes is off, and there goes your wine.)

And that’s before we get to the horrors that climate change is inflicting. Droughts, deluges, forest fires.

Once-in-a-lifetime disasters are happening yearly now. (Good job, human race!)

They don’t even need to happen to you directly.

Imagine there’s a fire. It’s happening near your plot, which is worrying, but it doesn’t end up getting to your vines. Are you good?

No! Fire destroys the habitats of multiple creatures, who will be starving and looking for shelter. The first to run off and find somewhere to feed will be the birds. They will come for your fruit. Hopefully just some of it, so you’ll still have enough left.

Then deer may realize that there are some tasty leaves right over there, and hey, look, grapes! But they are not going to eat the whole plant, right, so ideally they’ll “just” decimate your vineyard.

But if there’s a fire, this will also scare off boars. Boars are big, clumsy, hungry things. Boars will rampage through your plants and fuck them up - if you are lucky, they’ll only uproot them, not trample them as well.

But hey, maybe you dodged not only the flames themselves but all three, and the animals went in a different direction, or the disaster wasn’t close enough that you are the best option for them or, sensibly, they were trying to avoid the smoke.

Yeah. Smoke. If your vineyard gets covered in smoke it’ll completely destroy your grapes’ flavor. There goes your harvest. At least if you get too much water one year, you might be able to sell the grapes for food, or for cheaper wine. If they get smoked, you are throwing them out. It’s going to make you wish you had gotten the boars instead.

Maybe none of these happen to you, though, and you have a few sane years.

You still have to contend with producers who not only have established channels, brand recognition, a marketing budget that is more than you spend on entire production, and who produce between hundreds of thousands and millions of bottles across a wide range of price and quality, which chances are also covers whomever you were hoping to target.

How do you plan for this? How do you even set yourself up for sustainability if the Plagues Of Iberia I just mentioned are perhaps (horrifyingly!) the easiest to foresee?

This sounds insane

Through the years I’ve developed a relatively high tolerance for risk. And with my risk tolerance, and the fact I fully acknowledge the role of luck in my being able to stand here talking about it… even so, this sounds insane.

How do they manage it?

So I gotta say, I’ve developed a lot of respect for these people, how they show up and focus on the few key things they can influence.

And I think it’s worth examining how they go about things, because while not everything might translate, seeing how other industries approach problems we face can help us view things more impartially, because we don’t bring the assumptions we would to a domain we know better.

It can give us ideas, and it also helps examine mistakes people make in other areas.

Branding

Yes, branding

And we are starting with branding.

The reason we are starting here, is because it is perhaps one of the few things they get to think about in advance. When you are starting on a wine project you don’t even know what you’ll have to work with come harvest time, a year later, but you do get to think about you want to be perceived.

In fact, we should think about it more as character.

Character can do a lot of heavy lifting for you.

Being remarkable, being easy to create associations for, will go a long way. So if like myself you aren’t crazy about the B word, then think about it this way:

There’s a fair chance you’re not thinking hard enough about what character your efforts project. Because more and more, it’s becoming exceedingly clear that the scarcest thing out there is attention.

Now, even though it’s probably unconventional to tell you during a talk that you should be listening to somebody else, I would recommend everyone watches Austen Collins’ story of the Serverless framework, from MonkiGras 2017, where he goes into packaging as storytelling, and how having an opinionated approach to things can let your choices tell a story for you.

That’s something the two wine makers we are going to look into tackle in different ways (and arguably sometimes overshoot the mark).

Pies Viejos

You could go traditional, familiar. That is what this team, called Pies Viejos, is doing.

You see any of these bottles in a shelf, you’re going to recognize that they’re from the same house.

And if you have had one of them and liked it, you’re probably going to think “I should try this out this other thing over here”.

This familiarity is going to remove some of the discomfort that people feel around selecting a wine, where you are often asking people to go with an unknown quantity. It’s something that’s even worse in software, where people aren’t committing to trying their luck with a bottle but to spend at least a few hours or weeks evaluating an option.

It’s also something we won’t have enough time to go into, but happy to chat about it later.

And they did an excellent job of it, I think. Leaving aside the bottles, there’s a unified language to the design that one can’t help but appreciate.

This unified view, this progression, translates even to the wine. Three of them are made with the exact same grape, just from different parcels, aiming for a different result, and the design helps tell you that these three are related.

What’s in a name?

And they do follow Austen’s advice and try to tell you a story with everything, down to their name. But they make the mistake of telling that story only to those “in the know”.

For those of you who don’t speak Spanish… Pies Viejos translates literally to “old feet”.

Given the mental image that most people have of wine is a bunch of villagers stomping on grapes… that might not be the first image you want to convey.

Now, if you happen to know a bit about wine making, then you know that in this case the word “foot” refers to the rootstock of the plant - but that’s something the average Spanish speaker might not know.

So what Pies Viejos means is that their vines have old roots.

This is relevant because back in the mid 19th century, a pest coming in from the Americas blighted European vineyards, attacking the plants’ roots and injecting a toxin that killed them.

Entire vineyards were about to disappear, and the only way for most vineyards to survive was by taking American roots, which were resistant to that plague, bringing them over, and grafting their own plants on top. You ended up with new feet and old bodies.

Having gotten all that background out of the way… the reason why Pies Viejos picked that name is because they have vineyards that were not affected by phylloxera. Their whole vineyard, from root to leaf, is of old European stock.

So if you know about the whole bit with the phylloxera and the feet and what not, Pies Viejos is a sensational name chockfull of information and character. If not… it might come across as weird.

The morale there is: If you are thinking about how to name your project, be it wine, or a framework, it might behoove you to check the name with people outside your immediate sphere - or at the very least explain the why in your other communication.

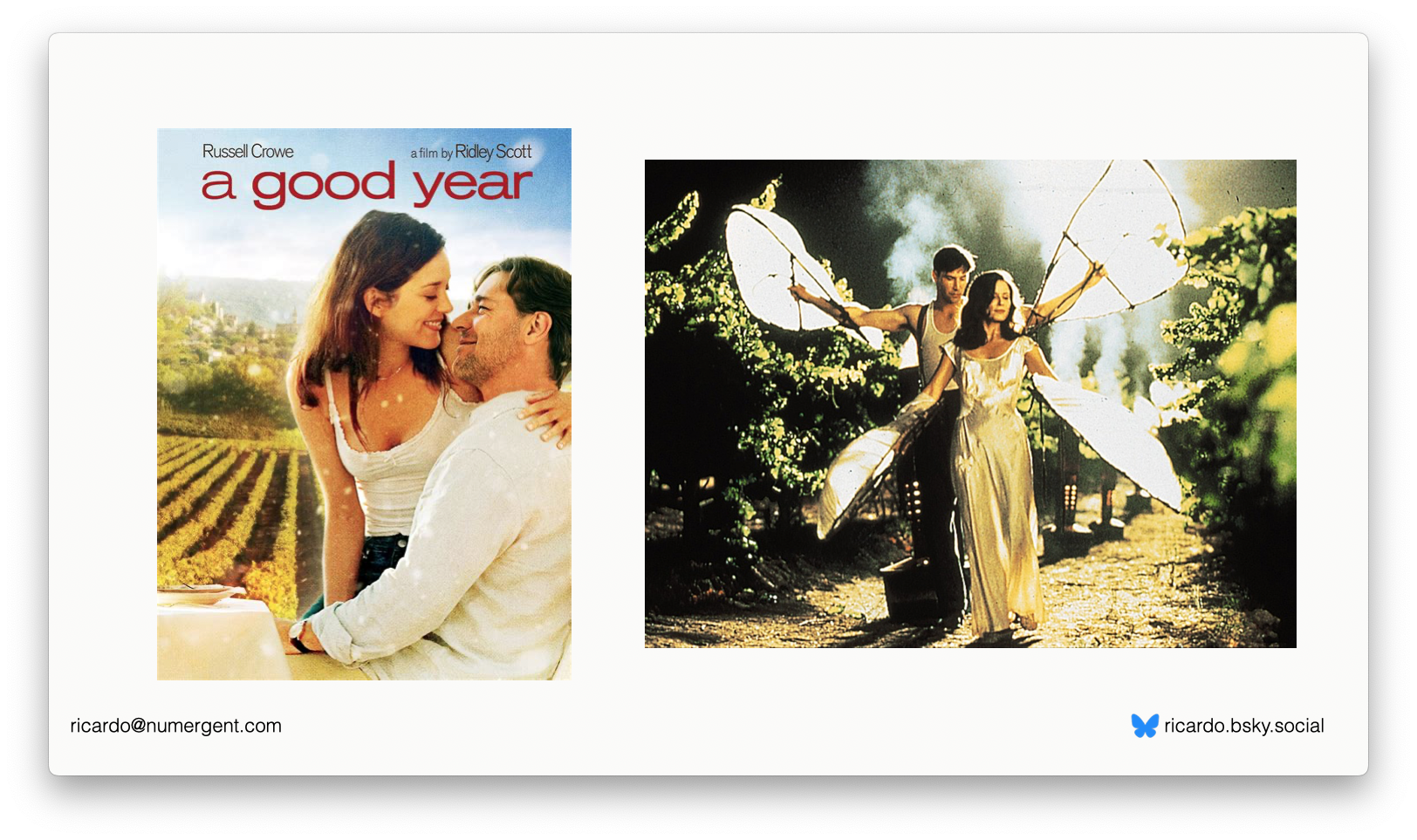

Enter The Malandrín

Whereas Pies Viejos is clearly going for brand recognition, Maladrín seems to be optimizing for something different.

Maladrín wants every single bottle to have a personality. Which fits with their brand. Their slogan is “vinos únicos” - unique wines - and by god do they deliver.

Roberto’s stuff is iconoclastic. Even the brand name is idiosyncratic. A Malandrín is a brigand, a hooligan. And again, it fits - their wine feels like it’s picking a fight. With Every. Single. Bottle.

His wines are definitely opinionated.

Particularly Malandrín Superior, this one right here, with the screaming faces. It wants your attention, doesn’t play well with others, and it’s a multi-faceted wine that keeps changing as you let it air. It’s a peculiar creature.

But that thing I was saying earlier about wine being threatening, intimidating for people?

I mean… look at that thing. The bottle may fit the brand and the wine style quite well, but what does that tell you as someone reaching for it?

And about what we were saying about encoding a story on your branding?

I’ve seen people grab this bottle and ask “what the hell is this thing?”

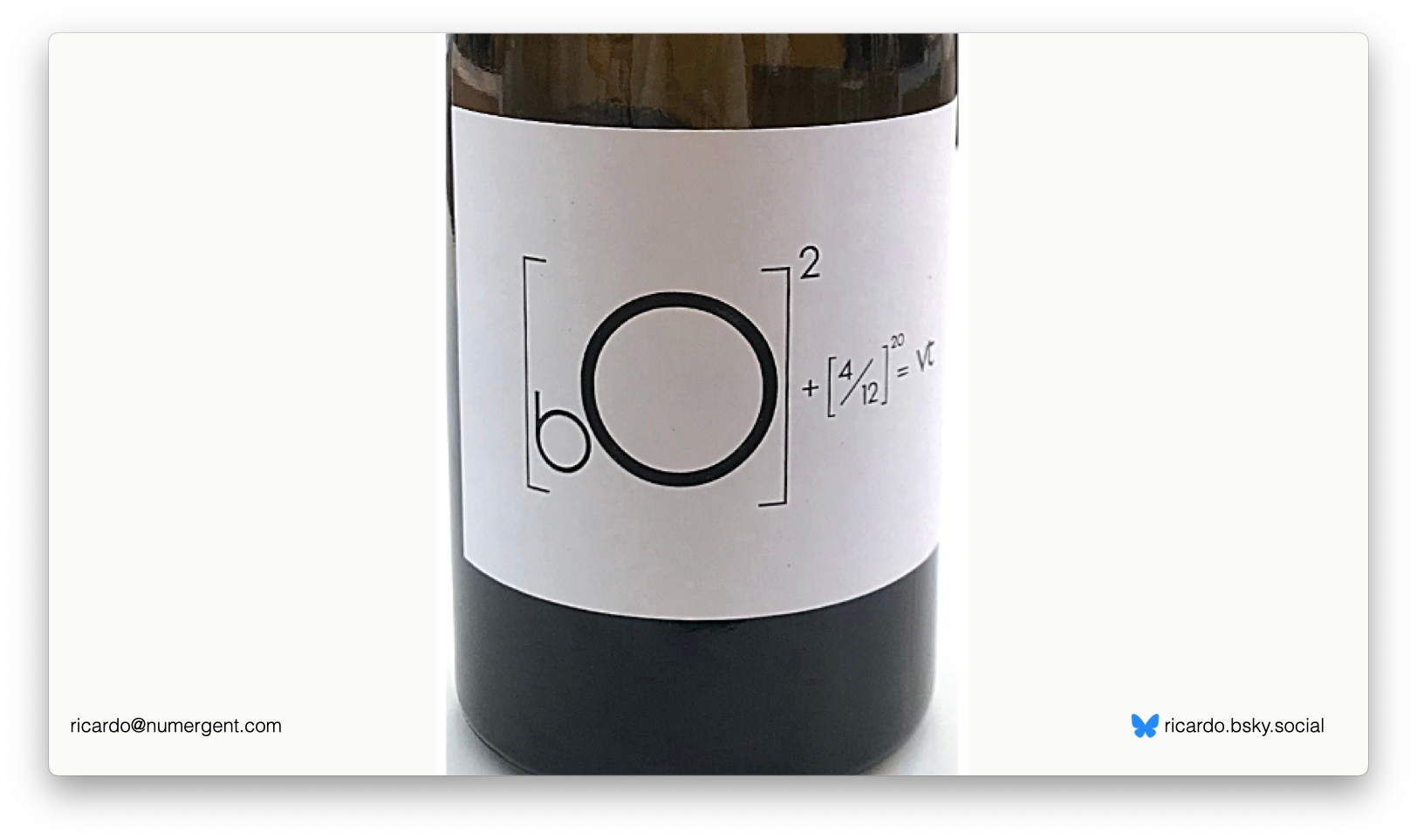

And I can tell you what it is, because I heard the wine maker talk about his choices with the wine and connected them with the label, but I mean… … nobody who hasn’t had that conversation and who doesn’t know a bit about mathematical notation is going to get it.

The name is bobo, so bo-squared; it’s a late harvest wine, so instead of picking the grapes in the usual August/September time he did it in December (and I’m guessing December 4, 2020), and late harvest is “vendimia tardía”, so vt

So yeah, that encodes a lot of information, it tells the wine’s entire story and the choices that were made during its production, and absolutely nobody is going to know.

Brazenness

I’ll give Roberto this, though - communication issues aside, not only he is a sensational wine maker, he is bold. There’s a character to the stuff he puts out there, a brazenness, and nowhere is this more evident than a particular wine that he makes differently every year, his “experimental” batch, called “El Vino de mi Pepino”.

What that name means is “the wine from my cucumber”. Now, in case you think this is some idiomatic expression and that I’m translating it literally just to be funny…

Nope. I’m pretty sure that’s the mental image that he’s going for.

Be bold

Now, there are two lessons we can get from the existence El Vino de Mi Pepino.

The first, and obvious one, is to leave room for experimentation. There are lessons Roberto gets from his even weirder wine that he can apply to future years of his more regular bottles.

But the second is there is a brazenness to El Vino de mi Pepino that just demands your attention.

Going back to Austen Collins’ talk, he tells the story about how they even had branding positioning them directly against Docker, with the docker whale floating dead in the ocean with a big bite mark on it.

That’s brazen. That’s something that would not only make people remember you, but that it tells them what you stand in contrast of.

(He also mentions why they ended up not using it, but that’s a another story)

Labels matter

And speaking of how you want to be perceived… there’s a lot to be said for honesty.

Open Source

Pet peeve here.

Look, much as I like to think of myself as an open source advocate, I get it if you think that if you use an actual open source license for your project, and it is successful, Amazon is going to take it, paywall it, and cut you out.

If you feel the need to use the Business Source License for your project, go ahead - it’s your company, it’s your employees’ income you’re risking. I don’t get to judge you for the license that you pick.

I will judge you, however, if you attempt to call yourself an open source company while using something like the BSL.

Communication, meaning, trust

Because labels matter, because they carry meaning.

They bundle up a bunch of concepts in an easy to digest manner so that people know what to expect from you, and a key part of sustainability is people knowing they can trust you in the long term, that they don’t have to worry about continually looking under the hood to see if you have altered the terms of the agreement.

And this is something that I quite respect from the Pies Viejos guys.

I normally don’t like natural wine, and I know that probably kills any wine hipster cred I may have been building up, but it just tends to not work for me. Like I may find a bottle every 12 months that I enjoy.

When I tried their orange wine, I actually quite liked it.

Now, this was me being ignorant, but I thought all orange wine was natural wine, merely because that was the case for all orange wine I had encountered, so I congratulated José Carlos, one of the partners, on making a good natural wine.

And he does this very aw-shucks-y reaction.

“Oh, we don’t do much to it, since we do touch it a bit, I couldn’t call it natural - I call it low intervention”.

Now, he’s doing this at a time when natural wine seems to be everywhere, and labeling his wine as natural would likely not only allow them to charge a premium, but make it stand out for people who don’t normally like natural wines.

Most consumers wouldn’t even bat an eye at the distinction, because the term gets used interchangeably, and I assure you that a good chunk of wine store people I’ve spoken to don’t differentiate between the two.

Pies Viejos, however, are choosing an honest label even though it at the very least leaves money on the table for them, and I respect the hell out of that. It means I can trust him in the future, which makes me a lot more likely to remain a customer.

Money

Now, I know what you might be thinking. These are wine makers. It’s an industry. It’s something you make money from within a year or so, once the bottles are out, unlike the massive initial build up and financial risks we take on software.

Let me disabuse you of any notion about wine being something that you get into in order to make money.

Economics

You see, Malandrín Superior retails for about €26. That might not be much in London - and I know it’s pretty much barely above starting price for a decent Californian - but in Spain that is already pitting you against some stiff competition. The average Spanish drinker would be taken aback by the thought of buying such a bottle blind - and that’s not a wine you’re going to find by the glass.

That means your audience has now further narrowed down, because for a lot of people, buying by the bottle is a commitment.

You will not be moving volume. Which might be just as well - Roberto didn’t remember how many bottles he produced that year, but he was sure they were less than 3000.

At that production volume, you are not going to be able to get into the main department stores, because they will expect at least a few pallets.

So you are left with finding a distributor, and getting it in the hands of consumers who might be curious, maybe selling it yourself directly (which both Pies Viejos and Malandrin do).

A distributor will take between 30%-42%, which is already above the Appstore’s extortionate percentages.

(Unlike Apple, the distributor does have to work, though.)

Let’s average it at 35%. That means out of the €26 you are left with €17. But wait, there’s more! Spain has a 19% VAT! That leaves you with €13 per bottle, meaning if you did end up making 3k bottles, and each and every one gets sold at full retail price, that’s about €42,000 you end up getting for your entire year’s production.

Correction: Spain actually has a 21% VAT

Not as profit, mind you. That’s before you even start covering costs. And hopefully the large plot of land that contains your vines just fell into your lap, and you’re not paying off some loan, or decided it would be a sensational land investment.

Oh, and by the way, the Bobo VT or a few of the Pies Viejos wines are more in the 600-700 bottles produced a year.

That is why my friend Roque like to say that making wine is a very classy way of losing a lot of money.

Why would you?

And you get to run the risk gauntlet every year.

So… given you are going to be getting less out of an entire year’s harvest than a mid-range Javascript developer gets without having to buy a plot of land, picking grapes (which is a labor-intensive process that will destroy your back), expose their income to whatever elements and plagues the environment might throw at them, deal with byzantine local regulations and production councils for your region (and trust me, I’m not going into that to avoid this becoming a rant against absurdities), finding the right distributor, and somehow conveying the message about what you are creating without (chances are) ever having met most of your customers… why? Why would you?

Because you are driven to do it. Because it is something you derive intrinsic value from, and which will hopefully pay for some of its costs. And sometimes, because you happen to find the right allies.

Allies

Roberto, from Malandrín, seems to be the lucky solo founder who still manages to make it work.

Pies Viejos, on the other hand, is three people: José Carlos, a Spanish industrial engineer; José Luis, a Venezuelan Electrical Engineer; and Carlota, a radiologist.

They not only teach about wine, pour all the time they can and energy into this project, but as far as I know they all practice their main professions - because how could you not, with those economics?

These things are, in practice, side projects that just also happen to have a massive starting cost.

And that’s something we need to seriously consider when we think sustainability. Maybe a lot of what we start will remain purely a side project.

Set yourself up for the long haul

Now we did have an entire Monki Gras batch around the theme of “homebrew”, how a side project ends up becoming the main thing.

They are some sensational chats, ranging from Nick O’Leary talking about defending Node-RED at IBM to Kent Beck interviewing a couple of guys from a microbrewery. If we are talking about lost skills, we need to get better at revisiting our recently generated knowledge. I strongly recommend you watch them.

Just be warned that it might instill some survivorship bias.

Self-awareness

And perhaps that is one area where winemakers do have it easier.

Maybe in software it’s all too easy for us to convince ourselves that if we just sacrifice enough hours, if we deal with enough entitled users being shitty on Github issues about their feature requests, or those strange pull requests they want merged, maybe the project will get big enough that it brings in the money and we get to do it full time.

We can more easily tell ourselves that with just enough sleepless nights and lost weekends, we can leverage what we have put in indefinitely, because of the magic of not having to deal with unit economics.

A winemaker doesn’t get to deceive themselves this way.

They can eyeball a plot, figure out how many plants there are, and with some high school arithmetic be able to guesstimate how much money they are likely to end up making in a year, assuming no major disasters and being able to make the most of their production. They can easily figure out “yeah, I need a partner, and I can’t just hope the right market will materialize”, and “I probably shouldn’t leave my main radiology job.”

Self-deception

I suspect this self-deception about scalability is something our industry encourages, including expecting you to apply to jobs with your Github contributions, because - hey! - free labor!

But you need to shake that idea. Chances are what you are doing won’t scale - not its creation, at least.

If you are passionate about what you are making, you need to realize that you are better off prioritizing your own long-term sustainability than deluding yourself about the chances of whatever you are working on reaching critical mass.

Which again… maybe means these things are just side projects.

Be calculating

I feel I need to say this given we now have billionaires bitching that everyone under them doesn’t work hard enough nor spends enough hours in the office, so here it goes:

I am not saying that you should be working nights and weekends on these things “if you really wanna succeed”.

Passion is really easy to abuse. It is a place where someone can sink a hook into, and take advantage of you, just because of how strongly you feel about what you are working on.

It makes it easy for someone to tell you how happy, how privileged you should feel that you get to work on these things day in and day out, overtime, while being in the office at the very least during weekdays.

So what I am saying is the more passionate you are about something, the more calculating you are going to have to be about it, just to make sure you can keep doing it for as long as you want to.

You don’t want someone else’s impositions turning it into the wrong kind of passion.