Introduction

My goals for this talk are to:

- Give a small taxonomy going into categories and labels that I think are useful when talking about identity;

- Walk you through what a layered conceptual model for identity could be like;

- Talk about the privacy implications for how we go about implementing things;

- Hopefully convince you that the closer to the edge we process things, the better it is for the user, but that the edge does not guarantee privacy (no matter what the Blue Behemoth whose name starts with an F would like people to believe).

Before we get too far…

Let me clarify one key point here, before we get too deeply into the weeds.

This is both a work in progress and a collaborative effort. There are a few people involved on some areas that we’re discussing today, both from Samsung NEXT and outside, including a bunch of us who met at the Internet Identity Workshop. I expect more people to get involved as we progress.

The reason why I’m making this remark early is not just to give credit to these people.

I also mean to drive home the point that this is an on-going topic. We are all still figuring things out. There is no set-in-stone approach I can suggest or a good textbook I can refer you to.

This is not master class, it’s an attempt to spark conversation.

Definitions

What identity is

Identity is everything that defines you.

Identity is how you identify yourself not only to a random site, but to other people.

It is how you perceive yourself and how others perceive you.

It is the core of your life.

Digital identity is what emerges from the sum total of everything you do online.

That hardly narrows things down, though.

Let’s get down to specifics and start naming things.

We have two major components of online identity: facts and characteristics.

Facts

Facts are specific atomic details we know about an individual. These are elements that will generally fall under personally-identifying information.

They run the gamut from the name you go by, to username/password pairs, to shipping addresses, to phone and passport numbers.

This aspect of identity generally relates to verification and authentication.

These can self-asserted in some cases, like username/password pairs or phone numbers. You don’t need a government to confirm what my phone number or e-mail address might be - you can just verify it yourself.

We are calling these self-asserted elements identifiers.

Other elements will only be considered valid if they are backed by a trusted third party, or are presented in a medium that’s hard enough to fake that the person verifying it can trust it.

If there is any sort of external validation, we call them credentials.

Notice that some values can fall on both categories, depending on use.

Amazon trusts me to enter the right address from my apartment, because it’s in my best interest to actually receive the stuff I paid for.

You trust my name is Ricardo, because … what do you have to lose if it’s not?

A bank, however, would not trust either of those elements unless they are able to validate them as credentials. Their entire business would suffer if they take as a credential something that they can’t eventually substantiate.

Characteristics

But on the other hand… while my name is Ricardo, that is not who I am.

The who I am part of my identity is a lot less structured, and a lot more mercurial.

A lens on who I am is the technologist working on investments who writes talks that combine movies and the tech industry.

Another is the anime fan with an eclectic music taste that skews towards prog rock and synthwave.

Yet another is the very private person who’s made incredibly uncomfortable by even stating those characteristics to an audience.

There are aspects of this identity which have been there for decades but others have changed with the years.

When we are talking digital identity, these characteristics are what emerges from your daily activities online, what can be scryed from your data exhaust.

Characteristics can have a lot of value without identifiers, as we’ll see later.

If you know I have a strong interest in anime, and have a general idea of how that preference skews, you don’t need to know what my name is or where I live to sell me the right t-shirt.

This means that where identifiers and credentials have to deal with authentication, this aspect has a much larger impact on areas ranging from behavioral patterns to monetization.

Whenever I talk about identity in the aggregate, you can expect I’m talking about this aspect.

Granularity

But then, you’re all builders. I imagine you’re thinking “yeah, that’s nice, but it’s still not granular enough”, so let’s drill down a bit further.

An OSI-like model for identity

You are probably all familiar with the Open Systems Interconnection model, but let me do a quick intro just in case.

It is conceptual model meant to organize the functions of a telecommunications system in a series of abstraction layers.

There are some basic expectations. Every layer:

- Serves the layers above it,

- Is supported by the layer below it,

- Communicates with layers at the same level.

This is a great model for figuring out where does a new system or component fit.

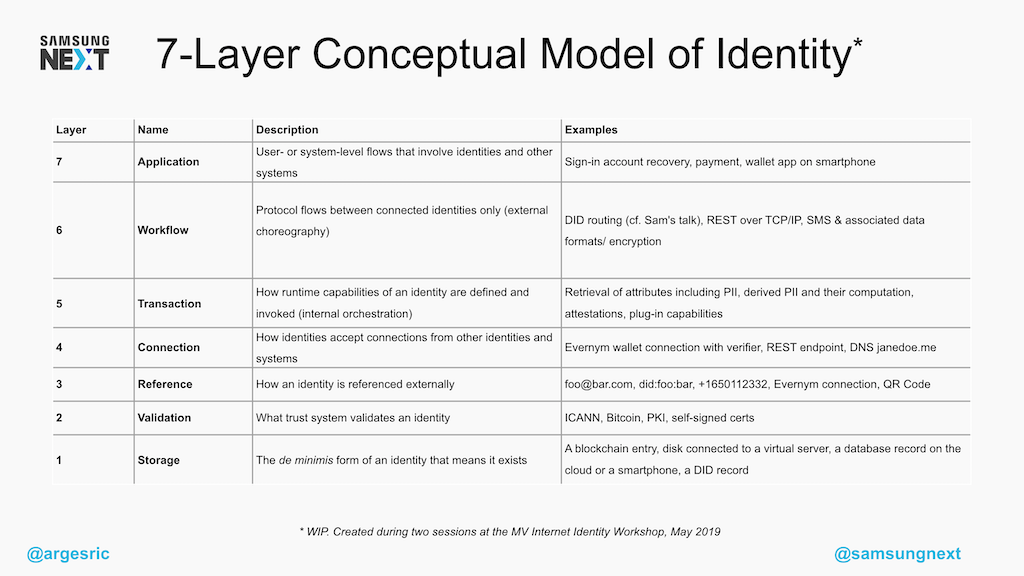

I’ve seen a couple of stabs at designing an equivalent for identity. A bunch of us tried as well and came up with our own version, which we feel is more general.

I’d like to reiterate that this is very much a work-in-progress conceptual model. This is not a standard, this is the result of six or seven of us mucking about with concepts for a few hours.

Remember that the OSI model is not just a layered stack - it’s also about how systems interact, or which layers we could swap for a different but compatible implementation.

Let’s go over a couple of these, because unfortunately we don’t have that much time.

The first layer down here, Storage, is pretty much all identifiers and raw characteristics. We need to have this data stored somewhere.

In theory we don’t care very much where, but if you ask me (and I know you’re just dying to ask me) I’d say this needs to be in the user’s control.

We’ll talk more about that when we get into the privacy topic.

But chances are identifiers need to be validated for them to be useful, turning them into credentials, which is why we have the second layer: Validation, or the trust system associated with the identity.

This validity will sometimes be self-asserted: for instance, if I give you my phone number, you can trust me or call me.

In other cases it will be built-in: if I’m sending a username and password pair to a site, the site itself is the trust system because they have the (hopefully) hashed and salted equivalent.

On the other extreme, you have the case I mentioned earlier, where the trust system is provided by an external party like a government institution.

Now, those are just storage and expectations. Obviously, before we can talk about or validate any of these things, we need to be able to Reference them.

And this was an interesting one. My first impulse was seeing foo@bar.com as the basic unit, but as someone else pointed out, both foo@bar.com and did:foo:bar can be references to the same underlying identity.

The reference can change, even if the two layers below it remain the same.

We can talk offline about what we see fitting into the other layers. You’ll probably see that the further we go up these layers, the least defined these things are.

That is because identity is relatively recent topic - as an industry, we are still figuring things out.

I expect other people will come up with different models, and we’ll adjust things as the industry evolves.

Even so, we created this because we need to have a vocabulary when talking about these things. Having a common vocabulary simplifies communication, and communication is fundamental for getting things right.

Why we need to get this right

And we do need to get this right, as an industry, because the design of your online identity has fundamental implications on privacy.

There’s currently a mad scramble by Gargantuan, Ginormous, Gigantic Goliaths to redefine privacy as

“We’ll take all your data and just not sell it directly”

Under that definition, you will have privacy because it’s only them watching your every move. It’s not like that other company, who shared your data with others. Those other people do evil.

On the other hand, the Blue Behemoth is looking to pivot into a “private” social network.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

Everything will be encrypted, they say, and any processing that needs to be done will be done on device (that’s the edge!) so Facebook will have no idea what you are talking about or what you’re into.

Well…

“We’ll data mine you but not share it with anyone” is adorable.

It is, at best, what an acquaintance calls “pinky-swear privacy”.

If that’s what you’re into, and if you trust that:

- The other side will keep their pinky-swear promise of not being evil,

- They will properly implement controls over it so that no employee can abuse their power,

- They’re such infallible engineers that the data is never going to leak

- (not like, say, people who keep passwords in cleartext for well over a decade)…

Then that’s fine, I guess.

Just be aware that there is a non-insignificant level of trust involved.

And about your data being encrypted so Facebook can’t read it… well… I wouldn’t put too much stock on it until they’re no longer an ad network.

Edge processing can be privacy-enhancing, but it is not privacy guaranteeing.

Metadata can be more revealing than data.

Let me give you just five data points. Suppose you’re processing all my data on device, yet you know…

- I am online usually in the Berlin time zone,

- Which IP addresses my connections come from,

- That I got served ads that skew towards movies and anime,

- That I click on ads about cat food every 3-4 weeks,

- That I never click on ads about nearby KFCs.

I expect we’re all seeing a profile emerge. You do not need to have a full log of someone’s conversations to build a profile, and get a picture of how to sell them a president (or sell them on not voting).

(You know, hypothetically)

In this scenario, you wouldn’t even need to get the identity facts about someone, as long as you can learn everything about their identity characteristics.

This is, I believe, something for which we need technological solutions.

Make it better

If there are any lawyers in the audience, I can imagine them rolling their eyes and going “bloody programmers and technology being a solution for everything…”, but frankly, I don’t think we are going to be able to legislate or regulate our way out of this.

We already have regulation. We even use it.

It has had no effect as a deterrent.

On April 24th, Facebook announced that they expected to be fined between 3 and 5 billion dollars by the Federal Trade Commission over privacy issues.

That’s a record breaking fine.

And it had worse than zero effect.

Not only it didn’t have a negative effect, but their stock price shot up, increasing Facebook’s capitalization by $40 Billion.

The FTC may as well have given them a license for privacy invasion.

So we can add regulation to the list of things that aren’t going to help.

- Regulation and fines aren’t going to get us out of this mess;

- People won’t leave because of scandals or screw-ups (or they’d have done it already); and more importantly

- People won’t switch because your solution is more ethical - we already have those, and people don’t use them.

Keep that in mind if you are working on identity. For users to switch, not only your solution needs to be better, but it needs to give users a good reason: it needs to enable them to do something that they couldn’t do before.

Because identity is sticky. This stickiness manifests in the fear of losing their friends, losing their connections, losing the small trickle of updates about who is dating whom or how the grandchildren are doing.

It is also a fear of impermanence. People have become so used to handing all this information out to third parties, to this being easier than keeping it safe themselves, that they worry about what might happen if they choose a more ethical but smaller cloud service, and then this service goes away.

Self-sovereignty

On his book Who owns the future?, Jaron Lanier warns against your identity being locked into places like Facebook and Google.

His concern is not only that these places are privacy invaders which use your life as a raw material, but also the fact that if Facebook ever went into decline, billions of people would lose access to their contacts, photos, and the rest of the online life they have invested there.

His suggestion is instead…

“Government must come to be the place where the most basic online identity will be grounded in the long term.”

Jaron Lanier, Who owns the future?

I like and can recommend the book. Lanier makes some excellent points, even if I don’t always agree with him.

But this is… this is one where I vehemently disagree.

The root identity residing with anyone other than the user themselves makes them inevitably subordinate to whomever controls this root.

This might be unavoidable right now when we are talking about credentials like a passport, because the institutions that consume them (like banks) want them rooted in a government institution.

But that is not the case for online identity.

Online identity must be in control of the individual. It must be self-sovereign.

Self-sovereign identity is a talk in and of itself. I’d suggest everyone reads Christopher Allen’s article The Path to self-sovereign identity, where he outlines the principles that he feels are necessary for any identity system to not only enable trust in a provider but preserve a user’s privacy.

Because earlier I said that for users to switch you’re going to need to enable some new interaction, allow them to do something they couldn’t do before.

Even leaving aside that the fact that I think that Allen’s self-sovereign identity principles are a moral necessity, we can just be practical: self-sovereign identity is more likely to enable new interactions just because nobody else is fully doing it yet, so we haven’t started exploring it.

You will see that a lot of those principles boil down to the user being able to have a say in what happens and when.

For us to be able to absolutely ensure that, the users need to preferably be holding the data themselves, or at the very least hold the keys to this data that is stored elsewhere.

We need to move things closer to the edge.

The edge needs a humanistic focus

We usually limit ourselves to the baseline definition of edge that comes from edge computing: how close do you process a data emission to where it happened.

That’s useful, from a purely technical standpoint. But we need to start looking at our implementations and architectures with a more humanistic focus.

We should think not only about where we process the data, but about who controls that node and its output.

Facebook doing edge computing probably saves them a lot of aggregate data center processing power, but users have no control over the profile that ends up being uploaded for ad delivery.

For identity data, we are not talking about just edges in a network.

We are talking about people.

And if we want to empower them, we should architect our solutions so that control over the data, so that sovereignty itself, lies with these very same people.

This is, what I think, we should be building towards. So let’s talk.