Last week I had the privilege to speak at infiniTIFF Summit, a part of the Transylvanian Film Festival dealing with technology, storytelling and experimental narratives.

I wrote Stories We Tell Ourselves for the summit. Below is a slightly longer version of the talk I gave.

Introduction

Hi, I’m Ricardo J. Méndez. I’m the Technical Director for Europe at Samsung NEXT in Berlin, where we partner with innovators and invest in forward-looking deep-tech companies. If you’re working on something innovative, grab me afterwards because I’d love to hear about it.

That’s it for the business side.

My background is actually rather eclectic. I’m a software engineer, but I’ve worked on everything from systems dealing with sensitive banking data to the interactive space to game development.

So I’m here to talk about stories and systems and games.

The only problem with talking about a topic that you love is that you have too much you want to say about it. I ended up writing over one hour of material for this talk, then had to condense it as much as possible.

In the end, it all boiled down to this:

- Stories change the way we perceive the world,

- New technologies allow us to tell new types of stories,

- We’re not doing nearly enough of that.

Stories we tell ourselves

There’s this part of our brain that, if we scatter a series of disconnected events, it will try to build a cohesive narrative around them.

Sometimes we don’t even need several points. A single image can do it.

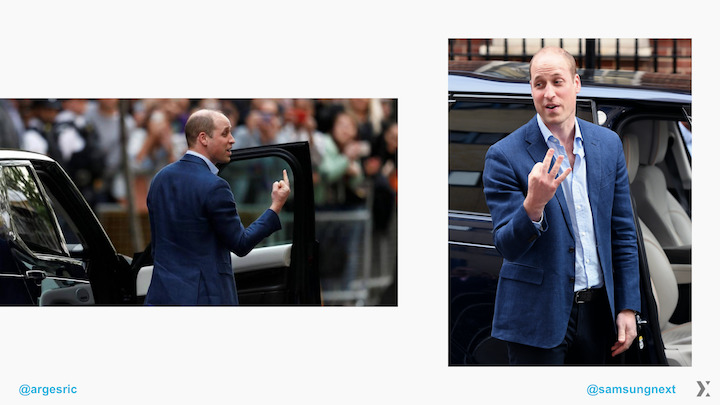

We see something like this, and we can come up with a few stories around exactly what’s going on.

I mean… spoiled royal, right? What are they going to do, fire him?

Because, guess what? Our brain just loves to jump to conclusions.

This makes stories extremely powerful, and it is something I’ll come back to. But first, let’s talk about how storytelling changed about 40 years ago.

Two and two score years ago…

Existing technology

I’m a voracious reader. I’m a movie nut. There’s amazing material created on both those mediums, but one issue with them is that ever since they’ve existed, they have been about passive consumption. You, as a reader or viewer, going through someone else’s material.

It all began to change with Sugarcane Island.

Sugarcane Island was written in 1969 by Edward Packard, even though it didn’t see publication until 1976. Who knows what it was?

It was a book, sure, but it could be so much more than that.

There were two significant innovations in it. First, the book was non-linear: you read some segments, reached a branching path where the book asked you to make a choice, picked a page depending on your decision, then continued reading. As you were reading, you were building up this unique story (or at least it felt that way at the time) which changed depending on your decisions. Some decisions added color, some had a major impact on the resolution.

This was a printed game. To get value out of it, you spent time partly as a reader and partly as a player.

It wasn’t the first book to try a non-traditional structure. Julio Cortázar’s Rayuela, from 1963, had a non-linear structure as well. Rayuela, though, was still very much a novel, just one that you could read in two different ways and with some optional addenda. You weren’t meant to choose - Cortázar had made that choice for you in advance.

The second innovation for Sugarcane Island was how it was written: the book used the second person. You found a cave. You decided if to explore or not. Your decisions changed your fate.

The combination of these two proved fascinating. It sparked an entire series called Choose your own Adventure. Anyone ever read one of these?

Now, this is a series of books for kids, but let’s not dismiss it off-handedly. These books used an existing technology in a new way, so that authors could get their readers involved in a narrative.

It had minimal interactivity - it’s a book! - but it was interactive. You chose. It couldn’t stop you from checking out all possible paths exhaustively, or backtracking when you got an option you didn’t like, but let’s be fair: most modern games don’t try that either.

New options

At about the same time - and I don’t know if there’s any causality here - Will Crowther and Don Woods were writing Colossal Cave Adventure.

Colossal Cave was the first piece of fully interactive fiction. It was a text game (because 1976) that presented you with a situation. It told you the environment you were in, mentioned whatever immediately caught your eye around it. You typed in a description of what you wanted to do and the game reacted.

It might present you with more choices, or ask you to clarify, or move you to a different scene, or tell you how you died because you did something stupid.

It could paint a much more detailed world than any game book, because it didn’t have to deal with page count or print costs, and could also react in unexpected ways, present puzzles, have you figure things out. Unlike in the books, you couldn’t peek ahead - the only way to do that was by dealing with the game on its own terms.

It was a leap forward on the way we could interact with a story.

It wouldn’t get as widespread use because, hey, it required computers, and remember that this was still the late 1970s. Those things were expensive and I don’t think we were supposed to be playing with them.

Even so, it still managed to change what we could expect from fiction, because it did something no other story had done before: it reacted! It talked back! It got snippy with you!

Adventure games

From Sierra and LucasArts to TellTale Games, the adventure game genre has exploded and contracted since.

We’ve had first person shooters and RPGs and open world games and visual novels, all the while the needle keeps flickering from player agency to passive viewing.

Some games stay true to a narrative formula while telling a heart-rending stories, like The Last Guardian, and some which run circles around narrative conventions while using known game mechanics like Nier: Automata.

But while in the hands of a Yoko Taro or a Fumito Ueda this linearity can produce masterful results, I’d say we’re squandering the medium’s potential.

We should leave more empty spaces, leave areas where people can tell themselves stories about what’s going on, because it is those stories that have more permanence.

Déjà vu

Let me tell you a story of déjà vu.

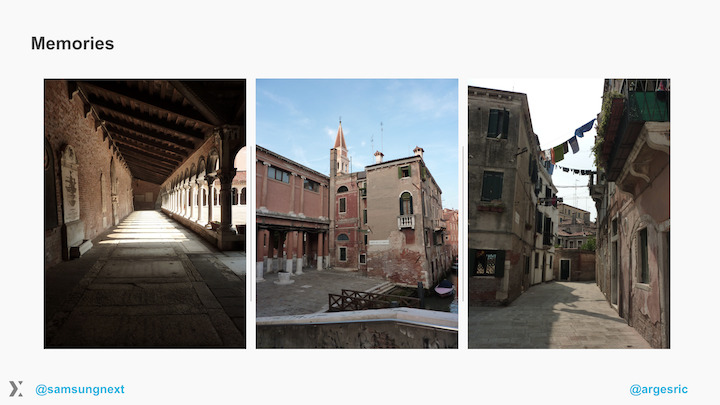

My wife and I are movie nuts, of course, so we decided to try the Venice Film Festival a few years ago.

The thing is, Venice is a labyrinth. You’re trying to get to a point which may be 200 meters away as the crow flies, but you end up walking a kilometer and a half because of all the winding streets and surprise canals that just pop in.

We spent a good chunk of the first day just getting lost, wandering around, building a mental map of the place.

Then we started recognizing some sections, alleys, open spaces. We knew that if we turned right here, and went into this little back street, there’d be another turn right after which would deliver us into a piazza.

It felt bizarre, though, because these weren’t landmarks. The alleys and areas we were recognizing weren’t places where we had been before.

Then the penny dropped, and I realized that I had to learn to navigate Venice before, when I was playing Assassin’s Creed 2.

Assassin’s Creed 2 is an open-world game, partly set in Venice. You get to navigate the environment as you please, and there’s going to be bits of story scattered here and there. People for you to meet, or work with, or murder.

When we were playing it, our actions always had a purpose. This made me focus on the environment. Moreover, you get to climb walls, do this whole parkour thing. I kept seeing these streets from a vantage point. Being up, in the rooftops, looking down, helped grok the layout.

This déjà vu was more pronounced for me. My wife had been sitting besides me as I played, because we did this sort of peer-programming thing where she kept an eye out for feathers that you can collect while I stabbed people in the head, but while I was a player she was just a viewer.

And learning the city’s layout was easy because there was a story I was telling myself as I navigated the sandbox.

I was building up a mental narrative.

This is where those guys cornered me. That’s the roof I keep getting pushed off from. This is the alley into which I can bait the pursuing soldiers.

We didn’t realize we were learning. We weren’t expecting this as we went to Venice, a few years later. We’d even forgotten about the connection.

Here’s what was really fascinating, though.

Ubisoft’s designers didn’t try to represent the city literally. Proportions were wrong. There were missing segments, so we kept finding sections that “weren’t supposed” to be there. The missing pieces, the things that weren’t quite where you expected, the expanded scale, ended up lending reality a dream-like quality, because we were used to the fiction.

The game had not only pre-loaded but re-wired our perception of the city.

This is something that could only happen because computers have gotten powerful enough that we can represent large swathes of a city in them.

It’s a start, but it’s not enough, because the narratives embedded on this game are still fairly straightforward: the only difference is that we get to explore in between scripted missions.

Emergent systems

Now, we also have this interesting gray area which is predicated on us telling ourselves stories. They are emergent systems.

It’s on this genre that technological exploration meets narrative choices. It’s a space I’m fascinated by because of two reasons.

First, it hacks into our need to make sense of the world, tapping into that same part of our brain that likes to make sense of isolated images and disconnected events.

But second, and even more important, is the fact that it actually uses computers to tell a story which could not exist anywhere else.

In an emergent system, the end result depends on local actions by multiple agents, instead of a unified vision executed top-down.

If you want a trivial example, think of an anthill. Nobody designs its architecture. It emerges instead out of the interactions between thousands or millions of individual workers.

On an emergent game, the designers came in, configured a set of (often very elaborate) rules, and then left you a sandbox to play with it. The world emerges from continuous application of and interaction between those rules, over and over and over.

A great example is Crusader Kings, by Paradox Interactive. More than almost any other, it’s a game made of numbers. It has been described by detractors as playing a spreadsheet, which if you’re being cynical, is not too far off, but dismissed the amazing complexity that can emerge.

It’s set in Europe. All of it. And parts of Asia and Africa, for good measure.

You pick a point in time to start in and a ruler. It could be Charlemagne himself or some obscure tribe chieftain. And off you go, making alliances, passing laws, deciding who sits on your council and which laws you enact, who you marry, while the world rages around you.

We’re talking about thousands of AI characters making choices with are then aggregated.

Let me give you an example of the things that can happen.

This is a multi-generational game. You run a dynasty, so it’s important to have good heir, because the moment your ruler dies, you’ll be playing that kid. Problem is that, much like in real life, you don’t pick your family. And you don’t control any character but the current ruler directly.

Suppose you decided to start the game in Spain. You’re running whatever part of Castilla you’ve managed to take back from the moors, while still fighting a Crusade against them, and your only son is less than ideal. You don’t want to be playing that guy.

One solution is to get your stupid heir sent to war, commanding the squad you keep throwing at fortresses, so that he gloriously dies in the line of duty.

That’s OK, because you have a mistress on the side, and she has a smart kid who you’re going to legitimize the moment the little useless son is dead.

Only he doesn’t die - the moors just brain him and render him incapable. And then your character has been pushing himself too hard and has a stroke.

So your wife takes over as regent while you’re still alive. She’s smart, because you married for her brains… but not for her nice temper.

The AI takes control of that character. Why?

Because you hadn’t managed to change your realm gender laws to Absolute Cognatic, so she cannot inherit. This is the same wife you’d been cheating on and it’s not like you were hiding it. She proceeds to dismantle everything you were trying to build, has the mistress and kid assassinated, all the while your character can do nothing but watch and drool.

This was just one of the many stories which happened to me over the course of single session.

There’s no cutscene I could play for you as a viewer. It was a series of decisions I made, ways in which the game reacted, dice rolled behind the scenes.

The story itself happened entirely in my head.

Crusader Kings is acting as a story-generation engine, using the number-crunching power of computers to spin out narratives that only exist because you, as a player, are interacting with it.

Unexpected emergence

Which brings us to this. We now find emergence and interaction where we wouldn’t expect it.

Back when Assassin’s Creed came out, Netflix was mostly known for shipping DVDs. Their unique selling proposition was not having any late fees.

They announced last year a plan to invest $8 billion on original content in 2018. Just let that amount sink in for a moment. That’s more money than the Marvel Cinematic Universe has cost since it started.

And as part of this investment, of course, we get a lot of series.

Stranger Things seems the clearer indicator of how we are going to influence the stories we are told. It hints at Netflix content eventually acting more like an emergent system.

Minor spoilers from season 1, if you haven’t seen it. There’s this (not even) secondary character called Barb who gets killed early in the series.

For some reason, people took a liking to her. This whole Justice for Barb movement started online, with people arguing her character had been treated unfairly.

This lead to a major subplot on season 2, where the driving motivation of one of the main characters is that nobody knows what happened to her friend.

An entire subplot of a 90-million-dollar production, created only because Netflix wants to keep you engaged, and people online were engaged with Barb’s fate.

These shortening cycles and direct fan connection will have a fascinating effect on narratives. ‘shipping has a chance of jumping from tumblr to the screen. Head cannon will no longer only stay in there.

Soon we’ll start expecting that we get to shape stories this way, if we don’t expect it already. We’ll start demanding the content that gets created is exactly the one that we want.

We’ve always done this, indirectly.

If a movie makes money, it’ll get a sequel. If a performer draws in a crowd, they’ll get more movies. But it’s never been this direct or this granular.

Data begets data. The better they become, the more users they get. The more users they get, the more they can afford to produce content tailored to a more granular audience.

They won’t always get it right, but they don’t have to.They only need to be right more often than not.

That way they can keep crunching data to find out which stories you’d like to hear, then make sure those stories exist.

This is why I mentioned earlier that Netflix will end up being an emergent system.

Even if the individual movies are (one can assume) still mostly author-driven, where the money ends up going and which movies end up the platform will be influenced by our choices as we play the game.

Along comes mobile

But this is not about Ubisoft or Crusader Kings or Netflix or me going to film festivals.

This is about a prime opportunity we have which I think we are squandering.

Did anybody play Rolando by HandCircus? It came out in 2008 - 10 years ago - and as far as I am concerned, it was the first game which truly took advantage of a smartphone.

You didn’t control these Rolandos by tapping on an on-screen joystick. You didn’t push bitmap buttons. You turned your phone this way and that, it detected the movement using the accelerometer, and thus you could lead them where you needed them to go.

Rolando understood the hardware. It created a world which could not have existed in the same way on a desktop or console or arcade.

Same old story

But when it comes to stories, I don’t think we’ve seen its equivalent yet. We haven’t seen truly mobile narratives. All we have gotten is the same storytelling, pared down for a smaller form factor.

There’s games which capture the feeling of mobile UIs just right, like Reigns. Not sure if you’ve played it. Like Crusader Kings, it’s a multi-generational dynasty game, only in a much smaller scale and using Tinder interaction mechanism.

You get a story beat, and you have some on-going stats, and you swipe left or right to decide what to do, and you get the next event.

This feels native, mostly because it uses UI language which was born on mobile, but this is still very much a yes/no Choose your own Adventure.

We can do much more.

Give me something new

Meanwhile, these things in our pockets have become supercomputers.

Galaxy S9 Specifications

Rolando took advantage of the accelerometer, which used to be the Big New Thing in hardware.

It’s not anymore.

Now we have 8 cores, and GPUs, and Near-Field Communication, and Wireless, and 4G, and multiple microphones and cameras, and more pixels we could dream of, and what are we using them for?

We’re using them to check Twitter and get outraged about how many fingers someone is holding up, just because the first image we saw happened to present a compelling story.

We can do better. We can tell people stories that could only exist here. Stories which are partly theirs and partly those of the people they encounter.

Stories where fragments and characters get exchanged via NFC or Bluetooth gossip as users go past each other in the street.

Collaborative worlds where people don’t have to consciously collaborate, but where the narratives they are building for themselves cross-pollinate with those from other people around them.

We live in an era of technological plenty. If you happen to have an Android phone, you have more access to the hardware than you’re likely to ever get with other operating systems.

Use it.

Use the technology to help us create stories which couldn’t exist anywhere else. Stories we can tell ourselves in ways we could not have done before.

Please.

I can’t wait to see these new worlds come to life.